I have a confession – and as far as the board game industry goes, it feels like a pretty embarrassing one.

Until recently I had never, ever printed a game from the internet. Not a card game, not a dice game, not an enormous eurogame. Other than a brief fumble with a 2 player Brass board which lasted all of 5 minutes (before I spilled coffee on the poorly sellotaped, badly folding cardboard), the world of print and play was something other people did.

Why? For the simple reason that the whole idea of printing games has never interested me.

I am not – and never will be – a proper craft person

I marvel at the work people can do with manual skill; at the things they can create with simple materials. But me? I will never really be a proper craft person.

My fine motor co-ordination is not great. Colouring in the lines, cutting things out properly and carefully measuring things bore me so quickly I find it tough to concentrate on them. I am impatient with instructional videos and guides. If this weren’t bad enough, my perfectionist aesthete streak makes me really unhappy with the shoddy job I always end-up doing with those kinds of tasks. It’s one reasons that I like prototyping in Lego so much. Lego always snaps into place perfectly; so there’s literally no physical skill in assembling it. What you create is actually a very pure, if primitive, form of art; the realm of ideas turned into directly into physical representations with no mediation of technical skill in between.

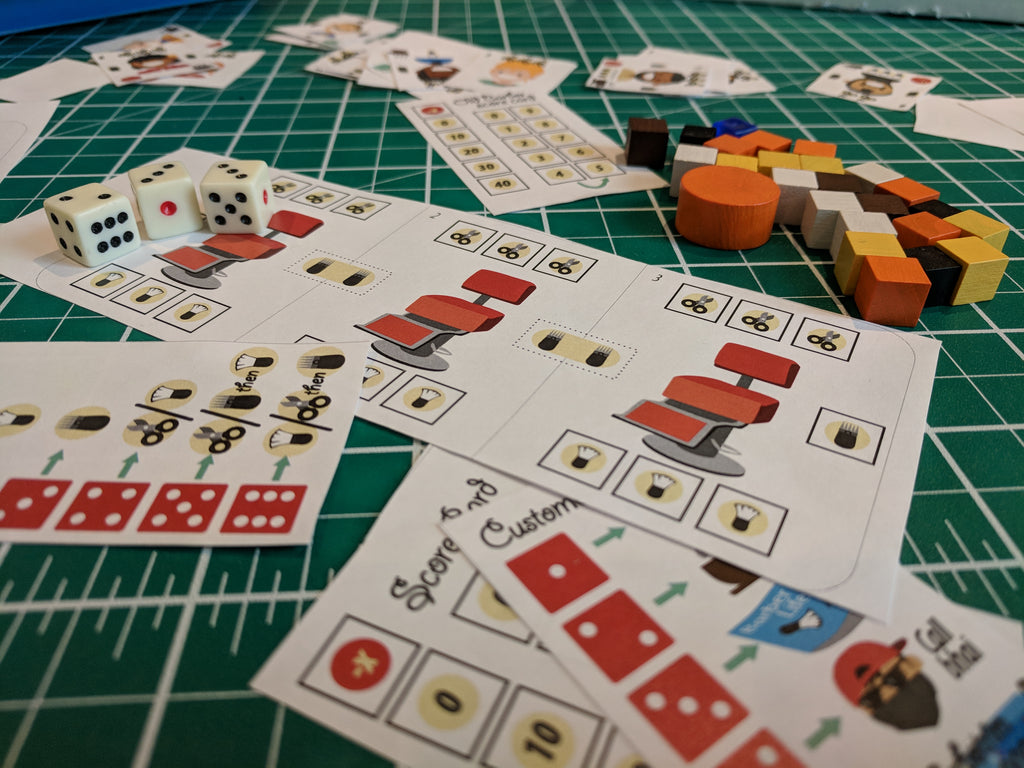

So the idea off printing a sizeable game, with all its myriad components rather than merely buying it, left me completely cold. When I make my own prototypes, I have no choice but to begin with simple black and white designs printed onto paper; scavenging whatever random wooden blocks or other pieces I can. But if it were remotely practical, I would totally make them sexy as hell from day one. The aesthetic experience is so important to me that I always feel a little bit sad that the game in my head is just so darn cool looking next to its bland, early-stage reality.

So when someone has already made the game for me, complete beautiful with wonderful artwork, satisfying well-tooled parts, all packaged up in a nice custom box, I can’t imagine ever producing it over buying it. That’s not just because I am lazy, technically inept or financially privileged enough to do so; even if I am all these things. For large games, the considerable expense in materials in making a nice version of a PnP game vs. the economics of manufacturing, can make them just as (or even more) expensive than the retail versions. And the labour, love and attention to detail required in producing a final game product just seems to be something worth paying for; for ethical and practical reasons.

The many other great reasons for Printing and playing

But when Magnate came along, I realised I could be a DIY game refusnik no longer. The more I researched the PnP concept, the more I discovered there were lots of other advantages to this type of distribution: for designers, publishers and hardcore enthusiasts alike apart from the pleasure of making.

1) Getting people to play your games

Finding playtesters is not always easy. While most people are up for a game, finding people that are in your target market is hard; and the reality is even your exceptionally wonderful game will never be loved by everyone. Finding people outside friends and family in that market who might be interested, harder still. And finding those strangers who will actively invest the time in playing an entire game is hardest of all. By turning your game into a format reproducible anywhere, you open-up your options to finding new players anywhere in the world. The PnP provides a powerful way to extend your testing pool. It’s absolutely not a requirement for success from what I have seen, but if you don’t have the people around you to help, it might be necessary for you.

If this is a route you choose to go down, it’s not enough to put any old export of your prototype up there. You’re going to need to make sure that the PnP version of your game can both be easily a) printed and b) (can you guess the answer?) played!

Doubtless some crafty thinking and testing required.

2) Getting people to test your rules blind

A variation on the first benefit, blind testing can be a very useful technique for making sure your rules are understandable even if your game already works very well. While you’re still there in the room to instruct people about your game, it’s easy to miss anything in the rules; even if you force your playtesters to read them. By providing a printable version, someone thousands of miles away can see pretty much exactly what it would be like to learn from the box.

I am still undecided about the extent to which some people treat this as a “gold standard” for the testing of games in general. This kind of testing does not yield a vast amount of crucial qualitative feedback that player’s can’t hide: how engaged they are, interested, bored etc; all the things which are best read in a person’s face than an email. I tend to agree with Eric Lang that in observing actual people (not even listening to them) is where you’ll learn about the success or failure of your game.

But there’s no doubt that this process has clear merits at the very end of the process, when you are testing explanation and documentation rather than the game itself.

But again if you want to do this with your PnP, for the same reasons as above, you need to engage with the process first and create a workable print-friendly version.

3) Helping other people with their games

The boardgame design community functions on a great deal of reciprocity and mutual support. Luckily, it tends to be filled with lots of lovely people who want to help. I am of the strong opinion that – quite apart from anything you get out of it – it’s a good of itself to help people by playing a game that’s still in development and providing them the input they need to make it better.

By printing out and providing feedback you can help make their designs better. And of course, they might just help you one day too!

4) Playing unreleased titles before anyone else

Part of me would love to spend ages discussing the psychological and sociological research that explores why we like getting new things sooner than everyone else. But this but this post isn’t about that; So I hope you’ll agree, for now at least that is is just fun.

But if you want to be at the absolute bleeding edge; not Kickstarter edgy but not-even-produced-as-an-actual-game-anyone-can-even-pledge-for edgy, and you don’t plan on doing any work, you have a problem. You’re going to need to be either a) be lucky enough know the designer, b) be luck lucky enough to playtest the game at an event. But With a PnP and a bit of effort though you can be playing a game long before anyone else reagrdless of such luck. A printer (your own or borrowed) and a BGG account might be all you need to get going.

It might even expose you to some new ideas. After all, all the production games are actually reflections of design thinking that are at the absolute least, 9 months out of date.

There was only one way forward

So there you have it. If I ever wanted to do a PnP for one of my own games, if I wanted to stay ahead and help other folk out, I had no choice but to engage with this DIY world.

In the next chapter I set forth, with some trepidation to (clumsily) make my first ever PnP games. Will it work out? Or will it be a disaster rendered in paper, sleeves and tiny, tiny wooden cubes?

Leave a comment