Thinking about running a Kickstarter? Well, 19 months after I decided to self publish my game, Magnate: The First City, I am entering the final build-up of mine. This is the inside story of the challenges, joys, thrills and spills of running a Kickstarter campaign and the nerve-racking final weeks before launch… read on if you dare.

NOBODY KNOWS!

Good! If you’re here just for the KS tips, you’re done with this blogpost already. In the chaotic world of the Kickstarter campaign, no one knows anything and its presumptuous to try to even work it out. You can get on with the rest of your day. Bye!

*James sobs quietly in the corner, filled with existential dread facing next month…*

Except… that’s not really good enough is it?

Kickstarter is a fundraising/sales platform in which you convince a people who believe in you (and your product!) to part with their hard earned cash on the promise of something awesome. I can’t think of any such commercial endeavour where it would make any sense to settle for that answer; no matter how terribly humble it makes you sound. How do you financially plan for that? How would you know what a reasonable manufacturing budget is? Most crucially, how would you begin to estimate you’ll achieve sufficient marketing reach to actually fund the project?

Of course you don’t know the number – it’s the future – you literally can’t. But it is your job as a business person (that’s what you are now!) to solve this problem and estimate it. As such a person, I am not actually sobbing (so don’t worry!). Instead, today’s post is inspired by the fact I have been working this very day on this problem, and have been updating my predictive model to solve just this problem.

But I am going to make you wait for the model itself. Today’s post is about the thing you can and should do early on. It’s widely accepted practice that I’ve summarised here and not just a piece of educated guesswork that is yet to be actually proved by the launch of my game. It’ll be critical for sanity checking your model if you choose to follow me down this path.

First and foremost: Look at similar projects to get a ‘ballpark’

A very straightforward way to work out a solid ballpark is what almost anyone will tell you to do: look at previous projects. It will only give you a very basic guide. But a basic estimate is always better than a shot in the dark.

Before I go further, it’s worth addressing that the number of backers and money raised are very different things. They are obviously intrinsically connected. But the relationship is complex and somewhat weak between game unit price and success: Both Kingdom Death Monster ($200 core pledge) and Exploding kittens ($20 core pledge) were monumentally successful raising $12.3m and $8.7m respectively. Their product, intended audience and price point couldn’t be more different. While basic economics will tell you that cheaper products will sell more units… perception of value is critical and too easily overlooked. I can tell you now with my product hat on (which is easily observed in the games world specifically) that an expensive product with a high core pledge that feels like great value will garner more backers than a much cheaper product that is perceived as expensive for what it is.

Crucially, if you have an approximately fair price for your core rewards you can use existing data to guide to guesstimate how many people you need to convert from a funding amount. You’ll see why backer number is really important for the second part of this post.

Getting a funding amount should start with data

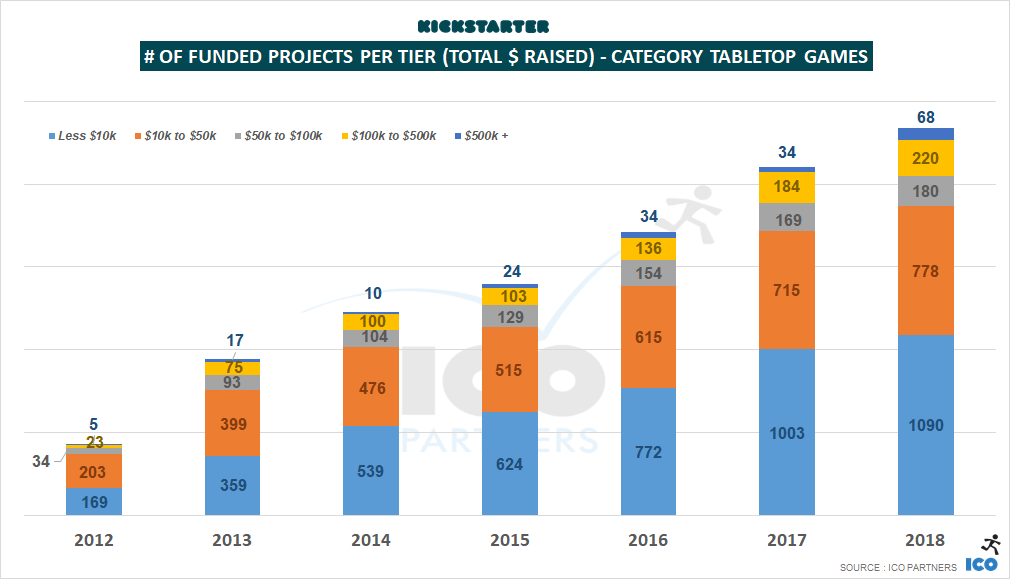

Datasets like this 2018 data set from ICO Partners can be a useful overview. You can see right away that the vast number of tabletop game projects are not raising many millions but less than $50,000. Out of 2,336 projects, only 68 raised more than $500,000 – ICO’s top tier category. Whenever I’ve closely examine those (just have a look at the top KS overall projects overall) it’s clear to me that they are doing so for basically three reasons (or a combination thereof):

- The companies involved have a long track record of making games (see CMON)

- The game is associated to an existing intellectual property or IP for short (A comic, a film or computer game franchise)

- A reprint of another more moderately successful initial KS or otherwise published game

So unless any of these is true of your project, I would personally disregard this tier entirely or the purposes of your project.

Below the very top, there’s a solid and surprisingly evenly distributed minority group of projects (400, approx 17% of all the successful ones) that raised between $50,000 and $500,000. If you bring your A-game, have a great product, a big marketing budget and are willing to put in a massive amount of work, this should be the top end of your reasonable expectations.

That’s still a huge range though and includes quite a few projects by big companies that were – for them – relative flops or only average performers. So they’re more limited success may still have been rooted in methods that only encumbents or companies armed with (often very expensive IPs) can exploit. So if you want to avoid disappointment, it’s probably best to think of the lower end of this broad range as your maximum bar.

Deciding any more exactly where your project is likely to land, is dependent – from my observations – on three more factors that, I think, are equally important:

- What similar genre games have raised

- How much budget/time you are prepared to spend marketing it

- Your optimism/pessimism bias

Similar games

The first is obvious but also I think the easiest to overstate. To have the best chance of success you absolutely need to research similar games to make your campaign as good a it can be anyway. If you’re making the dry euro I alluded to in the last post, these games are your competitor set. If you’re making a light, take that card game with a silly theme, it’s those kind of titles.

If this is your first RPG where you’re selling only a book your funding amount will be lower. Miniatures games can easily raise more money because of price point and KS’s reputation for miniatures games. But the problem is, from what I can see, that these two are among the most extreme examples and almost every other kind of game will fall between these. More importantly, what separates out the very successful from the less successful projects in any genre, isn’t the genre: its how well executed they are.

Budget

Marketing budget is a critical factor but also a fickle one. Projects that spend a lot of money on marketing will nearly always do better than those that spend very small amounts. But how much better is a matter of how good the marketing is, how well it is speaking to the game’s potential audience and a random luck factor no one can control (oh boy, if you don’t like the random outcomes of dice, you are not going to like this marketing business!). But if we assume you get it right, then you can only expect to get to those bigger numbers (the many tens of thousands of dollars) in one of two ways: pounding the pavements to kingdom come which is a personal time/opportunity cost (Joseph Chen of Fantastic Factories signed up 800 people to a mailing list from playtesting his game at small cons almost entirely alone) or by putting aside thousands of dollars for paid marketing in different forms (trade shows, ads, previews etc.).

Bias

If it’s easy to overstate comparison to other projects, it’s really easy to overlook the important of your own bias. Because this is all about estimation whether you’re an optimist or a pessimist will have a huge bearing on this. When I talk to pessimisst creators, they usually assume they’ll be in the bottom funding level (below $10k) despite the fact that a lot of these projects in this bracket have not actually executed that well (which can happen easily because this stuff is really, really hard – so no disrespect to them). When I talk to optimists, they tend more towards believing they will be the one in a 1,000 whose 1st time project will raise half a million dollars. They can do this with the same data or even their assessment of the same project. This is a problem because this affects every part of your estimation process: you will compare more or less favourably to others, believe your marketing efforts are more or less successful (there are limited objective metrics available on this) and simply back yourself more or less to smash the goal.

Whats to be done? Nothing much but make yourself aware of it. Entrepreneurs (which is what self publishers are) need to be optimists to keep going when the odds are massively stacked against them. Why? Because what they’re learning and the hard work they are doing as they go are, over time, actually shortening those odds. But financial planning is best done with a more pessimistic mindset because doing better than you thought is ,nearly always, much better than doing worse than you expect: generally only one of those costs you money you may or may not have to spend. Paradoxically, utilising both mindsets is important to success. Its up to the individual creator to to use them both to pick a figure they are comfortable with.

It can’t be overstated that this ultimately comes down to comfort. Whatever you decide will be a subjective melange of all of these factors. That’s not a bad thing – it’s still much better than nothing and I don’t personally believe it can be improved at this stage. Though please let me know in the comments if you have a reliable, proven method for this!

Calculating backer numbers

Let’s imagine you’ve decided the amount of funding you think you could raise, not your funding goal – which should only ever be your absolute minimum bar. You’ve pegged it at $30,000 and your core pledge will cost $60, working from an assumption that your manufacturing budget is really low and that your project can be profitable at this level. This assumption needs to be carefully examined in a budgeting process, but this can be a simple exercise as long as you have no especially expensive to make components (…unlike me). If you assume everyone goes in for the core pledge (which is pessimistic assumption if you have a deluxe one), then you will get 500 backers.

Is that it?

Yes! For now, it is. Remember what I said about price. As long as $60 is fair you can assume you will get some customers. If you had a cheaper product with an equally good product-market fit, you would get more backers because more people could afford it. But you would also raise less money per backer. So in my view, this relationship is a kind of constant. And where there is variation, its hidden – you can’t know how much more or less. As a result, simple division of your funding goal by pledge level is actually pretty legitimate approach to get this number.

Why is this number really important? Because now you have the number of customers you need to buy into what you are trying to do. That’s, in advertising language, the number of converters you must secure and immediately gives you a real sense of the difficulty (or ease!) of the marketing exercise involved.

In part 2, you’ll see why I think that’s also a really important number for my method of prediction.

Leave a comment