Can narrative and strategy ever blend well? Jaya Baldwin explores different ways games have tried to integrate narrative and traditional gameplay elements.

“Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin. Once upon a time in a land not so far away at all, a family sat at a table. ‘Now I convert 3 cubes into 2 cubes of net higher output’ said Mummy. ‘Wow, I adjust the resource monetizer on my personal board to rotate the value wheel to its next multiplier increment’ said Daddy. What a good time they were having playing Resource Cube Management Simulator. Little James and Sarah meanwhile had gone upstairs. They were sat under the big blanket with torches. ‘And then the princess took off her mask and revealed she was in fact the Swamp witch Anorax all along!’ shouts Sarah, delighted at her plot twist before James chimes in with some additional description about the Witches hair and complexion. What a good time they were having telling stories upstairs under the blanket.”

Narrative and tabletop games have often been separated like this. They’re assumed to be incompatible: the logic and objectivity of a strategy game could surely never accommodate the subjective whimsy and fancy of imagination? However some games have attempted this feat nonetheless, resulting in some very distinct gameplay experiences. From what I’ve seen, there are three primary styles of narrative application in games, each with their own merits and drawbacks and each is successful in different ways.

Style 1: The DIY approach

Games in this style focus on the imaginative and creative element of storytelling. Light on mechanics, often just providing basic prompts, they require the players to make the majority of the fun. The simplest example of this is Rory’s Story Cubes. In this game you roll nine dice that all have a different image on each face. You tell a story using all of them as plot or character beats, ‘spending’ them as you go. This is the extreme end of the spectrum. If players don’t create a story there is literally no entertainment. It doesn’t even have a win condition, so the experience lives or dies by the storytelling ability of the participants. This can be a challenge: I have seen many people freeze up in horror when tasked with entertaining a group like this. With the wrong crowd the game can easily come to a screeching halt; a flaw of this extreme end of the genre.

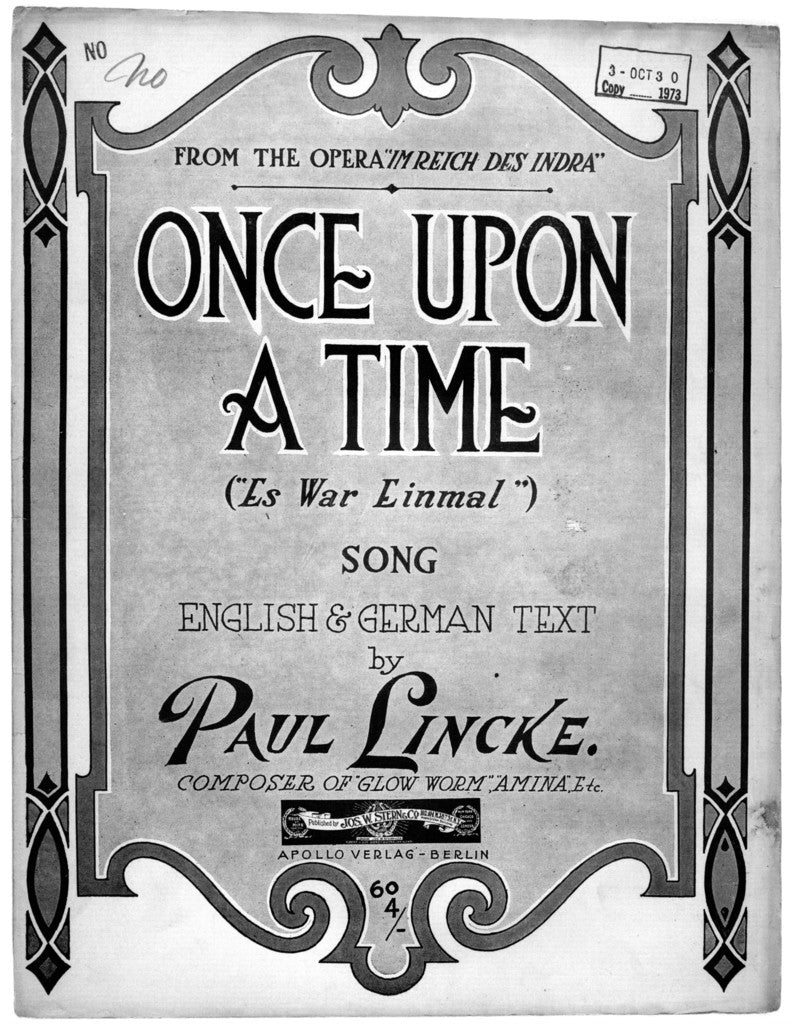

Some games go a little further in gamifying the storytelling process. Once Upon a Time introduces a simple game-based objective: get rid of all the cards in you hand. This is done by playing them to the table and integrating them into the story much like Rory’s Story Vubes. But it comes with the caveat that if you mention or describe something present on a card in an opponent’s hand, they get to play that card to the table and take control of the storytelling. This provides a little more player interaction but creates other problems. For example, for players that don’t enjoy the spotlight, there is still no mechanism to completely escape the need for improvisation. But for those that want to tell stories, the mechanics of the game actively discourage the telling of a good tale. The win condition incentives you to get all the cards in your hand onto the table as quickly as possible by mentioning their contents without straying anywhere else; for fear someone else will have that card and take control. That can result in stories that are more boring than they would otherwise have been; had the storyteller had a freer hand to meander creatively.

Funemployed tasks players with using a hand of cards with character and story elements to do something creative. Points are not given by the game but by the players. To win a round, you have to use your hand of cards to make a convincing pitch for why you suit the job role on the card that the rounds judge (or ’employer’) just drew. Once everyone has made their pitch, the employer chooses to hire someone on any criteria they like and give them that job card as a victory point. Because you can’t win without entertaining someone else, you are incentivised to put real effort into this pitch. Having one player each round choose a winner also means they are incentivised to be fair. If as the employer you were to give the point to a player based on their victory point total (for example), even though they their pitch was obviously quite poor, you know that the rest of the table will likely punish you in future rounds for foul play.

Style 2: Choose your own Adventure

The choose your own adventure category removes the impetus on the players to create story and instead has the game provide them directly; usually in the form of branching path choices that will have various outcomes.

Many games use this technique as a part of their overall design: the crossroad cards from Dead of Winter or the adventure portion of Above and Below. These short story segments are fun and add injections of drama – they are more or less important to the design but they are not the whole of the game by any means. Tales of the Arabian Nights however, is built entirely around this idea. Its adventure book contains well over two-thousand encounters for players to get stuck into as they wander around a world map completing quests in a bid to reach 20 points and return home to Baghdad.

Mechanics, once again, take something of a backseat. There are some rules to randomly generate adventures but points are assigned somewhat inconsistently; it’s actually possible to win the game just by staying in the same place. It’s a fun activity and the simple skill, quest, treasure and status cards lend a satisfying sense of character progression but I have never seen a single player actually care about the victory condition. It feels like it’s there just so the game will actually end at some point.

What the choose your own adventure style offers is a level playing field for all players. Those with creative flair still have plenty of room to improvise details and narrate theatrically while those who find that uncomfortable can play without such embellishments; reading out from the book in a straightforward manner and naming the actions they are taking; without seeming like the weak link.

From a design perspective, it seems relatively easy to create. The design is fundamentally modular and when choices are offered to the players they are specifically curated, allowing the designer to exploit fixed parameters to achieve balance. The challenge here, is actually rewarding skill. Any game where players are making decisions based purely on (occasionally vague) thematic inferences is always going to feel like a bit of a potshot. After all, how are you supposed to know the beggar you just tried to aid was going to secretly be a sorcerer trying to steal your life-force for his dark experiments? It’s fun but there’s few ways to play better either from strategic thinking or because you’re a good storyteller.

Style 3: Opt in

Games in this style feature stories very prominently but all the storytelling elements are, technically, completely optional. Both Gloomhaven and Arkham Horror the Card Game are both heavily narrative driven games. Without their stories and characters ,the thematic elements don’t really make much sense. However, both of them have been designed as incredibly solid co-operative games with interesting challenges regardless of narrative layer. Even if players chose to completely ignore all flavour text in the game, they would still be left with a rich and mechanically sound gameplay experience. I have played these games with groups which really get into character and roleplay the experience to it’s fullest. I’ve also played them with gamers who skim story text to get to critical information and play the whole game from a purely mechanical standpoint. These games hold up in both scenarios.

As a result, these games remove pressure on those uncomfortable with improvisation but don’t explicitly shut out those that want to use their imaginations more. That said, there are no gameplay rewards for creativity. Storytelling can enhance the experience but it won’t really change anything in the game. You can improvise the coolest sounding version of an attack you like but if the game says you missed and died, you missed and died and that’s that.

Leave a comment